Lately, Telegram has been flooded with spam, and probably everyone who manages a relatively large channel has encountered this problem. Strictly speaking, spam becomes noticeable at 500 subscribers, but once you hit 5000+, it becomes simply unbearable. I ignored this problem for a long time and was actively against traditional anti-spam methods like captchas, confirmations, and other pre-filters. From my point of view, it’s better to let spam through than to lose or annoy a real user. This worked for several years, and all I had to do was occasionally ban someone. But when spam became too much for manual cleanup, I decided to do something about it.

first steps

Obviously, the end product had to be a bot that would somehow understand what spam is and take action. Right away, an idea came up (suggested by bobuk) to use simple heuristics and consider anyone posting lots of emoji as a spammer. This pattern was quite fitting at the time since spammers often used an insane amount of emoji in their messages. So I wrote a simple bot that counted emoji in a message and banned anyone who used too many.

Of course, this approach is better than nothing, but it’s far from ideal and would clearly only bring temporary relief. But the core idea of using simple rules was sound, so I decided to continue in the same spirit. We noticed that spammers often urged people to “DM me” or “Subscribe to my channel,” so I put together a list of banned words and phrases and blocked anyone who used them.

trying to add third-party rules

The next step was to add support for an external service that collects spammers and provides their list. I found CAS, which answers the question “Is this user a spammer?” via a simple HTTP request. Adding support for this service took just a few minutes, and I was confident it would improve things. But unfortunately, it didn’t produce any visible results. My goal is to ban a spammer as soon as they show up, but in CAS they apparently appear too late. Most likely, they collect information about a spammer after they’ve already done their damage. As a result, I decided to keep CAS but not rely on it too much. Looking ahead, I’ll say that after the working version of the bot was launched, the CAS check caught no more than 10% of spammers, and there wasn’t a single case where only the CAS check worked and no other heuristic or classifier could have identified the spammer.

UPD: today (March 8, 2024) it happened — for the first time, the CAS check caught spam that other rules missed.

trying to add some AI

The idea of feeding text into OpenAI (when I started this, mainly GPT-3.5 was available) and asking it to determine how spam-like it was seemed promising. Technically there’s nothing complicated about it — come up with a prompt and send it to the API along with the message text. With great difficulty, I managed to get it to respond in a structured way, but the results weren’t great. First, it cost money — not much, but still. Second, accuracy wasn’t great — the false positive rate was unacceptably high. Third, it was slow. I abandoned this idea, though I returned to it later when GPT-4 became available. Its results were much better, almost perfect. If not for the dependency on an external service and its cost, I would have just used it and not bothered with other methods.

the approach of detecting messages similar to previously seen spam

This idea seemed promising to me. Feed in a few hundred spam examples (to start), tokenize them while cleaning out noise and short/common words, and calculate cosine similarity of each example with the message we want to check. If the similarity exceeds a certain threshold, the message is considered spam. This would be fast, cheap, and — as I thought — effective. And again, the result wasn’t particularly encouraging. Yes, the messages it flagged as spam-like were almost always spam, but when new spammers appeared who wrote in completely (or even slightly) different ways, this method stopped working. As a result, I didn’t abandon this method, but it became one of many, and far from the most effective.

what I should have started with — a classifier with training

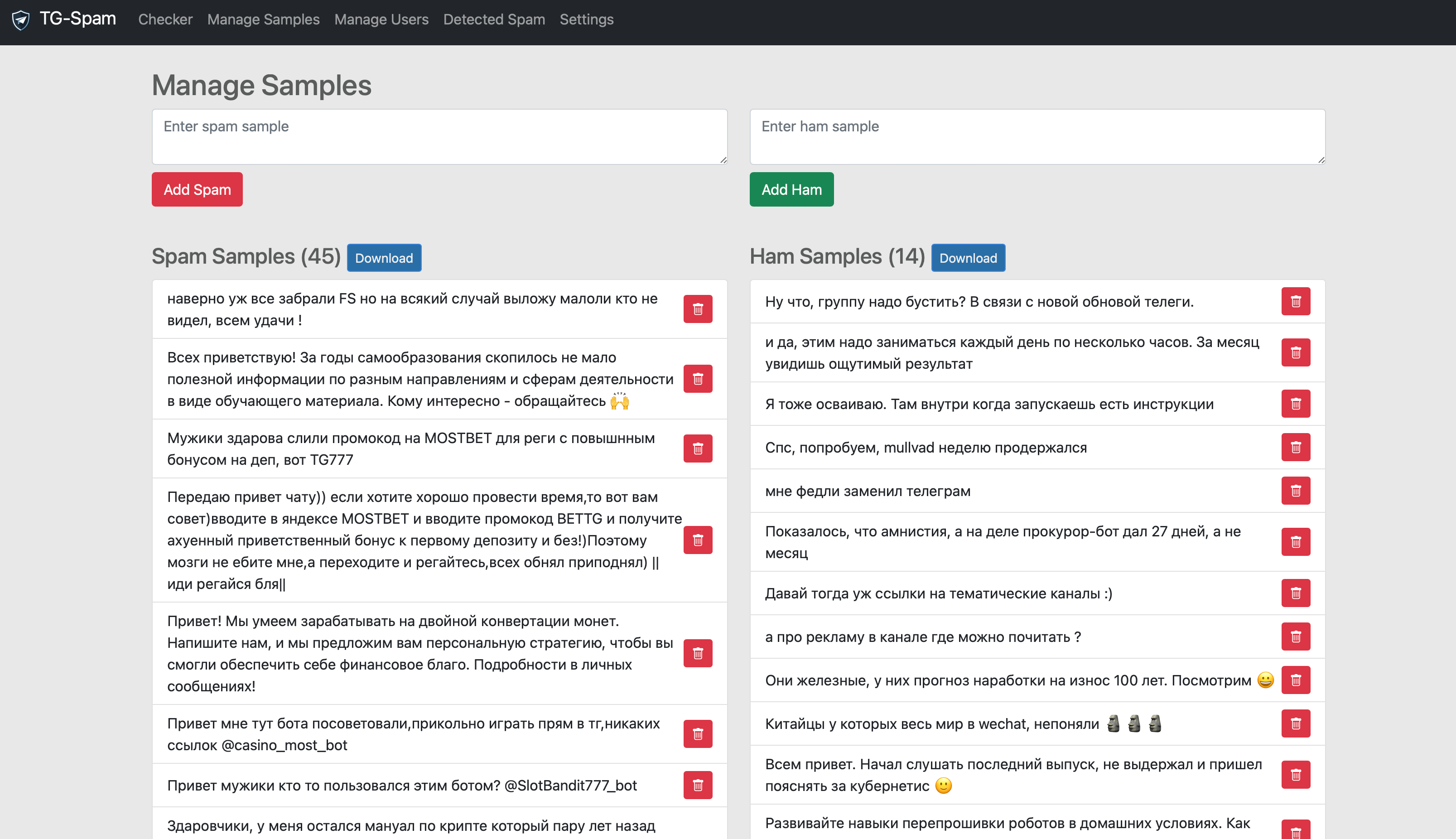

The thought that Naive Bayes would be perfect for spam/ham classification didn’t come to me right away. But when it did, I realized this is what I should have started with. The algorithm is simple and relatively fast — feed it examples of spam and not-spam and ask it which one the message looks more like. When a new type of spam appears that we haven’t seen before — add it to the training set and retrain the classifier. If there’s a false positive, add the message to the ham training set and retrain. This approach worked best of all, and I regretted not starting with it. Strictly speaking, this classifier alone would have been sufficient for 95% of all cases I encountered, but I couldn’t bring myself to remove all the other methods.

the finishing touch — detecting spammers by messages with insufficient information

This is mainly about crude, direct spam — lots of links but little (or no) text. Also messages with no text but with images. For such cases, I added a couple of heuristics that trigger on such messages — for example, if there are more links than words in the message, it’s spam. It’s a simple method, optional, requires no training, and works fast. I never actually enabled it since in practice it wasn’t needed yet, but it’s there just in case.

UPD: March 23, 2024 — I noticed real spam appearing with images and no text. Enabling the “messages without text but with images” detector, which I had been putting off fearing false positives, proved itself very well over a couple of weeks.

implementation details

I implemented all of this in Go, packaged it in a Docker container, and launched it on my server. The main classifier assumes that admins can add messages to the training set and retrain the classifier, so I had to integrate all of this directly into the bot. I tried to make management as simple as possible: to add a message to spam, you either forward it to a separate admin channel or simply reply to it with the /spam command. Then everything happens automatically: the message is deleted, the sender is blocked, and the message is added to the training set for retraining.

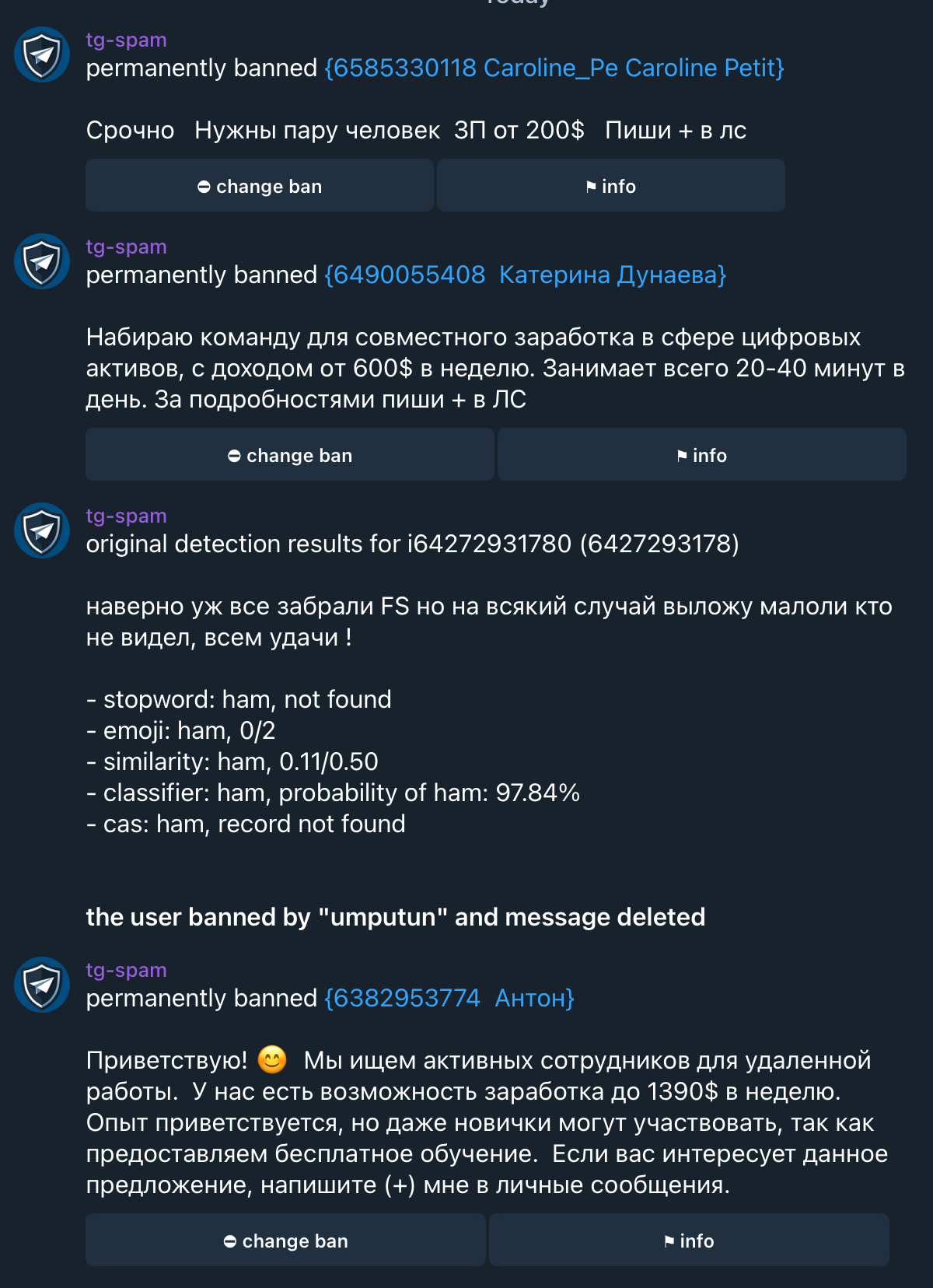

If a message was flagged as spam, it’s automatically sent to the admin channel, showing why it was classified that way with all available details. In case of a false positive, an admin can unblock the user with a single button press, add the message to the ham training set, and retrain the classifier.

Spam management example from Telegram

Another aspect is speed optimization. There’s no point checking every message from a user if they’ve already sent 10 messages and all of them were classified as not spam. Such users are added to a whitelist, and their messages are no longer checked. In practice, it turned out that even 10 messages is too many, since spammers who first send a few neutral messages and then spam are extremely rare.

To reduce potential costs of OpenAI checks, I made it the last step after all other checks. This check can be either decisive (if all other methods missed the spam) or confirmatory (if spam was already detected by another method), and in any case, it’s called infrequently. Again, there hasn’t been a need to activate this check yet, but it’s ready to go.

When I started using tg-spam and it gained active users besides myself, it turned out that the basic functionality sometimes wasn’t enough. As a result, a training mode appeared where the bot doesn’t delete messages but only marks them as spam/not spam, letting admins decide what to do with them. A feature for adding users to and removing them from the whitelist also appeared. I also added a “paranoid mode” where all messages are checked for spam.

The original version didn’t persist state (except recently trained spam/ham data), and any information like the list of verified users was lost on restart. While this wasn’t a real problem, in practice the need for persistence arose. Now it stores all data in SQLite, and everything is restored on restart.

I’ll note that writing the functional part of the bot was fairly straightforward, but implementing its interactive part was a real struggle. This was my first and, hopefully, last experience with all those UI controls that require jumping through hoops to get the simplest things working and were clearly invented by saboteurs to maximize developer suffering.

web interface

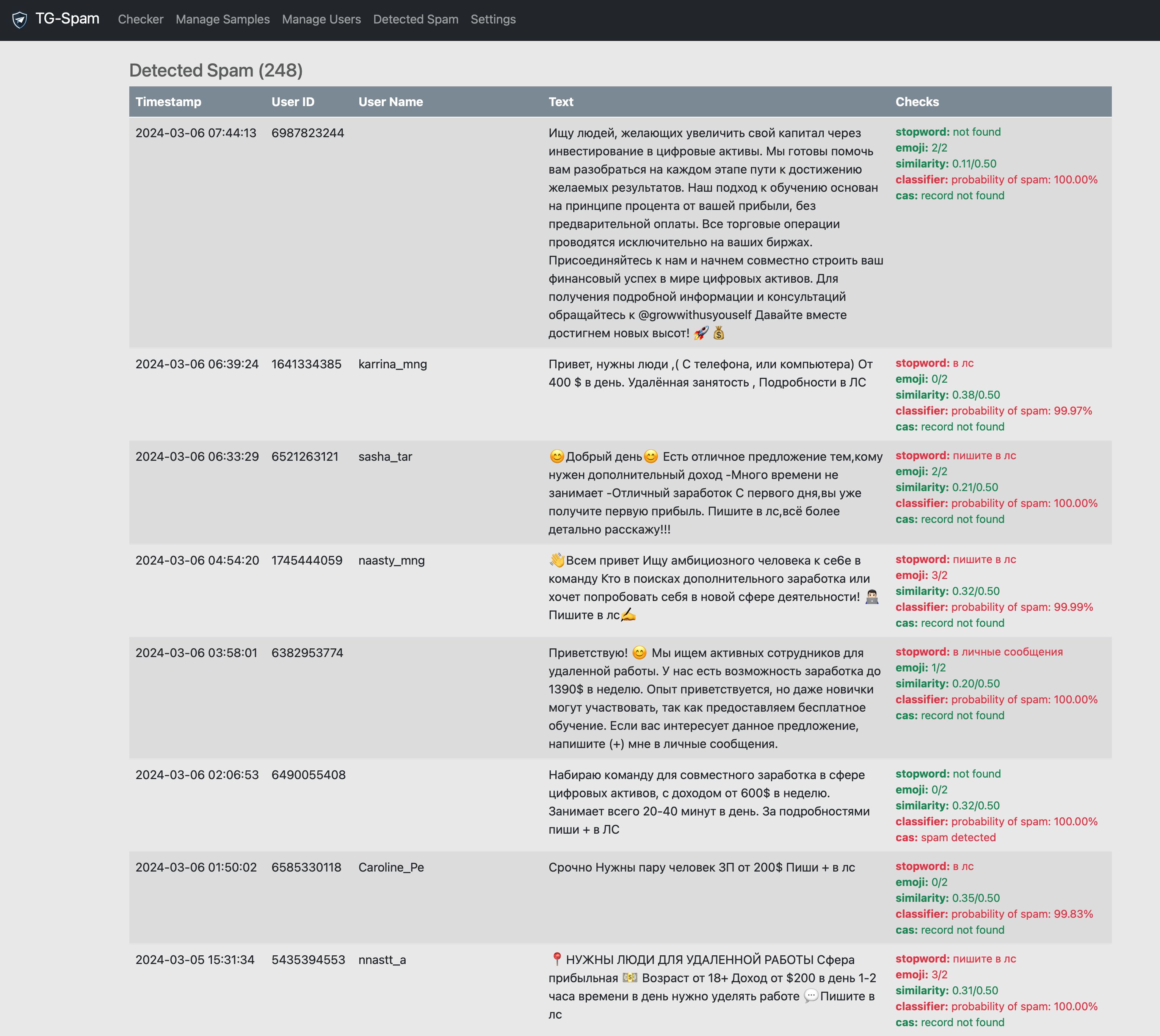

For admin convenience, I added a web interface where you can find all messages flagged as spam and see why. You can also add messages to the spam/ham training set and retrain the classifier. You can also test a message for spam and see how confident the classifier is in its decision and which checks triggered.

Web interface examples

results

I called all of this tg-spam, and the thing actually works, and works very well. The main problem with such systems is false positives, but I had very few of those. Of course, sometimes spam went undetected, but that was rare — only when a completely new type of spam appeared. Admins reacted quickly, added it to the training set, and after that all similar messages were flagged as spam.

Besides the ready-to-use bot that can be set up in 5 minutes, I also prepared a Go library that lets you use all these methods in your own code — for example, for spam detection in systems unrelated to Telegram. The service also has a simple HTTP API that can be used to check messages for spam and to add messages to the training set for retraining.

where to get it

This is an open source project and you can find it at umputun/tg-spam. You can grab either a pre-built Docker image or a binary. The code is available under the MIT license, and I’d be glad if tg-spam proves useful to anyone.

This post was translated from the Russian original with AI assistance and reviewed by a human.